Born at the end of the 1970s, I grew up attending Mt. Sion Church in Gyeongsan and Gyeongju, following my mother. On May 16, 2021, I became the third pastor in charge of Mt. Sion Church in Gyeongju. This year, on April 25, 2024, marks the 80th anniversary of the establishment of the Mt. Sion community.

Although many have written and spoken about the Mt. Sion community (especially focused on the Empire of Mt. Sion, 1944.4-1945.8), since my childhood, aside from Dr. James H. Grayson from UK, no one else has visited the church to meticulously interview the remaining congregants and review existing documents.

I grew up among the second generation who held memories of the first generation’s struggles. In this regard, my approach might not be vastly different from Dr. Grayson’s academic conditions. However, the difference between Dr. Grayson and me is not just a temporary academic interest, but rather, the existential and faith-based significance that the Mt. Sion Church movement holds for my whole life.

The history of Mt. Sion Church reminds me of the ‘Liberating God’ mentioned in the Bible, who freed the slaves from the Egyptian empire and brought His people back from the Babylonian empire, showing that the same God “is still alive” today. It was an existential and historical affirmation of God’s historical sovereignty.

To me, the experience of the Mt. Sion community, particularly the stories of liberation from the oppression during the Japanese imperial era, came with such meaning, and this historical faith in a “living” God has continually influenced my life.

As the pastor in charge, my current concern is how I can share this historical faith in the “living” God as a gift with others who live in the Earth. I am confident that the historical memories preserved by the Mt. Sion community will undoubtedly contribute to the living faith of future generations.

This article is a slightly revised version of a research paper I wrote while studying Systematic Theology at Yonsei University’s United Graduate School of Theology. It was an attempt to unpack theologically the memories of the Liberating God experience held by the Mt. Sion community, using German political theology and North American black theology as starting points. While it may have its shortcomings, I aimed to preserve the passion of the time with minimal adjustments, and for readability, I omitted the references.

Before proceeding to the main content, I would like to briefly introduce an interview with 99-year-old Deaconess Dong Soon Lee(19 Feb. 2023).

“It was during that era when I was 9 years old, attending school, and getting by somehow until I turned 14. At that time, no other girls in our village went to school, so the boys would constantly tease me about being a girl. I felt so strongly against going to school that I couldn’t bear it. When my mother packed my lunch, I would take it and go to a new house built on the roadside near our home, where a woman who had married into the neighborhood lived. I would eat my lunch there. After a few days of pretending to go to school, the boys told the teacher, ‘Dong Soon isn’t coming to school, you should check.’ My mother thought I was at school, but when she found out I wasn’t, she eventually had to carry my younger sibling and take me to school herself. But still, I didn’t want to go to school, and if you ask how far I went to avoid it, I even went as far as Pyongyang. There, I saw Pastor Joo Ki-chul. I witnessed the hardships the pastor endured and even saw his wife, Oh Jung-mo. The police in downtown Pyongyang gathered all the believing pastors and forced them to participate in shrine worship. They made them bow at the shrine, and I saw it all with my own eyes. After the pastor left, Pyongyang was a city of faith back then, not even opening stores on Sundays. Everyone was a believer. When the pastor’s family had nothing to eat, people would throw sacks of rice and bundles of money at their house. After the pastor was arrested and released several times, his wife said, ‘You must come out to die if needed, but it must be there, to withstand that trial.’ Eventually, the pastor passed away on April 21 (1944) in prison in Pyongyang. Despite suffering so much, he was buried on a mountain called Dolbak Mountain. His grave is still there. Later, I watched a film about Pastor Joo Ki-chul, but it did not capture even half of what I saw. He suffered unimaginably more. After that, I went to Pastor Park Dong-gi in Cheongsong. People said that if you wanted to survive and keep your faith, you had to go to Pastor Park. He even came to our home in the village once to conduct a service. I saw Pastor Park then, and later, 33 people, including him, were detained Police Stations, and were released after about three months. Then liberation came, and on August 15 and 16, we were freed. We slaughtered a cow and had a feast. At that time, there were people called the Manju Group from Cheongdo who were Mt. Sion Church members planning to go on missions to Manchuria, so we had a big celebration.”

1. German Political Theology and the Understanding of God within the Mt. Sion Community

1.1. Background and Development of Political Theology

Political theology is deeply rooted in the historical events of World War II under Hitler and the horrific Holocaust, which resulted in the massacre of six million innocent Jews. Although a minority of Christians tried to rescue Jews from the death camps, the fact that the majority of those operating the camps were baptized Christians led many theologians, who witnessed the Holocaust, to reject the traditional understanding of theodicy. In other words, the Holocaust was such a monumental event that the traditional interpretation of “the world’s evil and suffering being permitted for the realization of God’s plan” appeared to make God look monstrous. Therefore, the rupture with traditional theology became even more pronounced after the Holocaust, and instead of asking “Why did God allow this?” or “How can such events be reconciled with God’s salvation and reconciliation of the world?” the pressing question became “Where is God in all this?”

During this period, three prominent theologians emerged in Germany—Jürgen Moltmann, Dorothee Sölle, and Johann Baptist Metz—who all grew up under the socialist regime, directly experienced the devastations of war, and studied theology in the context of post-war German reconstruction. Their common theological stance was succinctly “theology that does not speak of God from the perspective of an abandoned, crucified individual says nothing to us.” They believed that faith, doctrines, and sermons not rooted in the harsh realities of World War II and the Holocaust were merely deceptions and idols. Thus, Metz argued that questioning God was not just a theoretical theological exercise, but a return to Auschwitz to speak about God.

These theologians, who later gained international renown, became friends and supported each other, and their theological thought evolved into “rethinking the living God in the midst of suffering,” encompassing not only the Holocaust but all the evil apparent throughout human history. Therefore, they began using the term ‘political theology’ to avoid avoiding the problem of suffering in intellectual thought, because it continually addressed God’s presence in the city and the public good among both the living and the dead. Political theology warns against a privatized form of religion that emphasizes personal religious experience and morality alone, criticizing the church’s failure to actively oppose Hitler and the complacency of a faith that failed to recognize an unjust social order. In other words, by highlighting the public aspect of religion, it aimed to create a broad theological perspective in the public sphere and encourage a responsible faith in God. Metz described political theology as “challenging the privatization of bourgeois religion, questioning God not in tranquility but while resisting the evils of the world, and emphasizing the mystical and political aspects of experiencing a suffering God.”

1.2. Formation and Development of the Experience of the “Liberating God” in the Mt. Sion Community

While German political theology blossomed in resistance to and reflection on Hitler’s German Empire, the Mt. Sion community was born out of the Christian resistance to the Japanese empires of Yoshihito and Hirohito. After Allen entered Korea as a royal interpreter for King Gojong in 1884, by 1909, nearly 950 Christian schools were established in Korea. This was because they followed the missionary policy of Nevius, a Presbyterian missionary in Shandong, China, advocating for the ‘indigenous church principles’ of self-support, self-governance, and self-propagation as the missionary policy of the Korean church. Thus, early Protestant missionaries in Korea emphasized thorough Bible study and memorization by the natives to establish a self-sustaining and vibrant church. In 1887, the North-South missionary routes of the Korean Presbyterian Church were unified, and the first organized Presbyterian church, Saemunan Church, was established. In 1907, 33 Presbyterian missionaries and 36 Korean Presbyterian believers gathered at Jangdaehyun Church in Pyongyang to organize the “Presbyterian Church of Korea.” By 1912, this assembly evolved into the “General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of Korea.” From then on, the Japanese continuously pressured the Korean Church to integrate it into the Japanese Christian Korea Church Association.

Amidst the gradual growth of Christianity, Japanese imperialism pushed forward its ambitions of continental expansion, heralding the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Starting with the Manchurian Incident in 1931 and the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Japan escalated its ambitions with the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, dragging the USA into World War II. Consequently, Korea was transformed into a logistical base for the continental war, mobilizing human and material resources for heavy industry, military manufacturing, and mining. In 1936, Governor-General Minami and Governor Yasudaki of South Pyongan Province spearheaded the “Clarify the National Body, Unify Inward, and Indoctrinate Through Hard Training for the Imperial Subjectification”(國體明徵, 內鮮一體, 忍苦鍛鍊. 皇國臣民化) to erase Korean subjects at schools, disband research institutions and newspapers like the Korean Language Society, Donga Daily, and Chosen Daily, thereby obliterating national culture and spirit. Moreover, imperial subject oaths were regularly recited in institutions, and citizens were forced to participate in shrine visits, palace worships, raising of the Japanese flag, silent prayers at noon, and wearing national and military attire. By 1938, the National Mobilization Law was enacted, declaring a wartime mobilization system that requisitioned food and lumber and confiscated metal items from households, including church bells. By 1940, “Soshi-kaimei”(創氏改名) forced Koreans to adopt Japanese names and surnames, further stripping away Korean identity. If Hitler’s German Empire aimed to destroy the Jews physically, the Emperor of Japan sought to completely annihilate the Korean spirit.

During this period of material and spiritual exploitation by Japan, the Korean Presbyterian Church, regrettably, succumbed to Japanese pressure. In 1938, during the 27th General Assembly, Pastor Hong Taek-ki was elected and resolved that “shrine worship is a patriotic national ceremony under emergency circumstances,” an egregious misinterpretation that followed the Japanese claim that shrine worship was not a religious but a national ceremony. The Japanese Governor-General’s office facilitated this by imprisoning leaders like Pastor Joo Ki-chul and suppressing dissent. After the Assembly’s resolution, Vice-President Pastor Kim Gil-chang led regional presbytery leaders to participate in shrine visits. This sparked a fierce anti-shrine worship movement, resulting in over 2,000 imprisonments, the closure of about 200 churches, and 50 reported martyrdoms.

The experience of the “Liberating God” in the Mt. Sion community emerged amid the suffering and chaos experienced by the Korean Church under Japanese oppression, with Pastor Park Dong-gi at its core. Park received his theological education at the Daegu Dongshan Bible School (precursor to Yeungnam Theological University), founded by American Northern Presbyterian missionary James Edward Adams (Korean name An Ui-wa) in 1913. While studying and praying there, in early January 1928, Park had a vision of “Christ’s cross and the love that forgives sins.” Mt. Sion Presbyterian records describe this moment:

“While praying, a blackboard-like surface appeared on the southern wall. White writing began to appear, detailing all the sins committed from ages 8 to 21—sins against God, sins in relationships with others, sins of the heart, and actions. Seeing the writing, he repented, wept, and lamented bitterly. Then, on the western wall, a bright white cross appeared with the gentle and humble figure of Jesus Christ nailed to it. He heard a voice of love saying, ‘By believing in me, you are freed from all sins. I have taken on all your sins.’”

This transformative experience through Christ’s cross deeply impacted Park, affirming the need for personal repentance and motivating his ministry as an evangelist in local churches. Park understood this experience in the context of Daniel 5:5-28, referring to it as “the glory of the cross.“

Starting in 1934, after graduating from theological school, Park traveled across the northern and eastern regions of Daegu, demonstrating his capabilities as an evangelist. In September 1937, a year before the General Assembly’s resolution on shrine worship, he was appointed as an evangelist in Pohang by the Presbyterian Church, where he began to openly denounce the enforced shrine worship by the Japanese. Subsequently, Park endured numerous interrogations and tortures by Japanese police, and was forcibly sent back to his hometown, Cheongsong. However, even upon returning home, Park did not succumb; he gained considerable renown as a preacher and became a leader of the dawn prayer movement, fervently opposing shrine worship. This led to further hardships at the hands of the police.

After being released from the police station, amidst anguish and conflict between reality and faith, Park decided to dedicate himself to early morning prayers near the tiger cave at Dodong Maesan. During this period, on November 29, 1940, while praying in his study at the parsonage, Park experienced another complex vision about “the destruction of evil, God’s intervention in human history, and the blessings to be bestowed on His people.”

“Suddenly, a powerful northwesterly wind from Siberia filled the heavens with a terrifyingly loud noise. As the wind noise ceased, the eastern sky above the mountain he was praying on opened up in clouds, and a green cross gloriously descended. Trembling in awe, he saw that this cross had even more dignity and power than the one he had previously experienced. Looking at the cross, he noticed a tree on the mountain shaking as if in a fierce wind. From the left side of the descending green cross, a northwesterly wind blew toward Uiseong, filling the sky with its sharp and forceful sound. As the wind ceased, he saw a radiant-faced man standing there, dressed in yellow ochre clothes without a cap, with a red stripe around it. From the right side of the cross, another wind blew toward Daegu. In front of him stood a person in green clothes, headless and lifeless. Then, from the Daegu direction, a sharp wind seemed to tear through the atmosphere, and something flew through it. As it approached, he realized it was a human head. When the head attached to the headless angel, the body suddenly came to life, its eyes flashing brightly, and it opened a Bible to show him. Park saw that it was Joel chapter 2. From the center of the cross, another wind blew directly into Park’s body. He experienced the rapture, reciting Joel chapter 2 in Hebrew.”

Park interpreted this vision as “the divine intervention in history leading to the destruction of the Japanese empire and the establishment of a new world order.” Based on Joel chapter 2, he further expanded his movement against shrine worship, even under severe Japanese oppression, attracting many thirsty Korean Christians to his cause.

Finally, on April 25, 1944, the day after the funeral of martyred Pastor Joo Ki-chul, Park publicly declared the establishment of a symbolic community named “Empire of Mt. Sion,” symbolizing the true empire of God’s kingdom against Japan’s false empire. According to one member, Jeong Woon-hoon, “The believers of the Empire of Mt. Sion fought as Pastor Joo Ki-chul had fought; while Pastor Joo’s fight was generally defensive, Mt. Sion’s was more aggressive.” This was because, although it was a symbolic act of the ‘Kingdom of God,’ they proclaimed the founding of the Empire of Mt. Sion with a ‘declaration of independence’ and completed a ‘political organization,’ effectively ‘seizing’ the state from Japan, and also determined their ‘national flag,’ during the severe circumstances of late Japanese rule when anti-Japanese movements were nearly impossible.

The Mt. Sion community understood this day in connection with the biblical ‘Exodus event,’ where God’s people were freed from the rule of the Egyptian empire, thus declaring it the ‘Passover’ of the Korean Church. They considered this day as the day they overcame the rule of the Japanese empire through the blood of the Lamb and emerged into the world.

The part of particular interest here is the subsequent history of the Mt. Sion community’s trials and liberation. On May 20, 1945, three detectives disguised as people wearing traditional Korean robes (hanbok) raided Pastor Park Dong-gi’s house while he was eating breakfast. They slapped his face, kicked his waist, took him to a corner of the room, hung him upside down, and tortured him by pouring chili powder into his nose from a kettle while demanding, “Tell us where the political organization book of the Thousand-Year Empire of Mt. Sion and the hymnal of the Lamb of Life are kept.” They also tortured him to produce a radio for contacting the USA and the UK, having heard that the Mt. Sion community was an anti-Japanese group actively involved in concrete actions. However, Park strongly resisted, and his wife was hung from a post in the annex for two hours while torture and persuasion alternated. Eventually, the detectives moved up to a radish field about 400 meters from Park’s house, arrested his colleagues, seized all the books, and transported the arrested individuals to the North Gyeongsang Province High Police at Loe-gyeong-gwan by 11 PM. Further arrests followed, and ultimately, 33 people were detained, undergoing interrogation amidst torture and persuasion. Particularly, Park was forced to wear a fountain pen on his hand and kneel while being incessantly urged to “become a loyal religious person of the Great Japanese Empire.” At that time, he stated:

“I am prepared to martyr myself for Lord Jesus Christ, so do as you please. Japan is a demonic beast nation, opposing God and will soon be destroyed. The UK and USA will be victorious. Even if I die, this statement is true and will come to pass. […] The abominable destruction of the Japanese empire, the victory of the Allied forces, and the future establishment of Jesus’ Second Coming and the Empire of Mt. Sion are all God’s will.”

Because this case was against the Japanese empire and based on a prophecy that the USA and UK would win the war, the local police headquarters felt too responsible and burdened to handle it directly, so they reported it to Gyeongseong(Seoul). Then, on June 8, 1945, an inspector from the Gyeongseong Governor-General’s judicial department came down to interrogate Park personally, stating after the interrogation, “We also have such spirit-possessed people(Kamikakari) in Japan,” before leaving the scene. After several more interrogations and tortures, on June 18, the 33 detainees were transferred to different provincial prisons, and it was later revealed that “plans were made to transfer the violators of the public peace law to Sinuiju by August 18 to execute them.” However, with Japan’s defeat on August 15, 1945, liberation came, and they were all released from prison, reportedly dancing with joy. A sermon from Mt. Sion Church describing this day stated:

“Psalms 102:20 says, ‘to hear the groans of the prisoners and release those condemned to death.’ In 1945, executions were ordered with just a phone call without trial. After the last confirmation by the judicial inspector from the Governor-General’s office, they were supposed to kill them, but they were dramatically liberated afterwards, and the pastor came out of prison and danced. ‘Releasing those condemned to death’ was experienced in every part of their being by God’s word.”

Three days after liberation, on August 20, 1945, the liberated community proclaimed the establishment of the “Mt. Sion Presbyterian Church” which occurred before the well-known branches of the Presbyterian Church took different paths from the existing Presbyterian denominations.

Meanwhile, the Mt. Sion community considers their experience of the “Liberating God” as their participation in the suffering and resurrection of Christ’s cross, and they continue to commemorate this day.

1.3. Reflection of the Korean Church Through Political Theology’s “God of Pathos“

German political theology arose as a genuine theological response to the experience of God’s absence amidst the reality of suffering and sin. Paradoxically, after experiencing the atrocious event of the Holocaust, theologians rediscovered the “God of Pathos,” who deeply engages with the world’s suffering. They emphasized a theological insight that “only a God who suffers can help us,” portraying God not as a distant, indifferent observer, but as one who willingly incorporates human suffering into His divinity, sharing our suffering as “God of Pathos,” as testified by the biblical prophets.

Under this view, Jürgen Moltmann developed a unique theological interpretation of the “crucified God,” while Dorothee Sölle and Johann Baptist Metz, although opposing Moltmann’s narrative style, walked a similar path by imagining a “God of Compassion” who stands in solidarity with all who suffer. Sölle articulated that “beyond sorrow and despair, those who partake in God’s suffering transform unresolved questions into a mystical resistance of a life of love,” asserting that “the cross of Jesus shows God’s constant companionship with those who suffer.” Therefore, “God, who brought the power of life encapsulated in Jesus Christ into our shared experience of death and suffering, was present in the agony of the concentration camps, and we are called to transcend the private sorrows and despair behind our service to God to truly partake in His company.“

Metz sharply criticized the focus on Christ’s resurrection without acknowledging the cry from the cross, claiming that “hearing only the message of resurrection without the cry of the cross is not hearing the gospel but a myth.” He spoke of a hope that “although the mystery of suffering is not yet fully revealed, it has already begun in Jesus’ resurrection and will be fulfilled on the final day.” Metz argued that “to have hope in Yahweh as the God of both the living and the dead, despite numerous defeats, is the essence of faith,” and ultimately, theology must start from the perspective of those conquered by unjust suffering to be truthful.

So, do we ground our theology in the history of the cross, in the history of God who shared in the agony of death, starting from our “Auschwitz”? Or is the current situation in this land more reflective of the proliferation of prosperity theology, which ignores the cry of the cross, and are we witnessing its end today? Is the “God of Pathos” truly alive in our theology?

According to the Fraser Report, President Kennedy noted that a former Japanese Army officer and communist led his country toward economic revival “for their political interests.” Along with this foreign-induced industrialization, the Korean Church laid the groundwork for the emergence of capitalist mega-churches. Members of the Mt. Sion community, under the shadow of a hypocritical dictator, were still being labeled as “communist sympathizers,” suffering in prisons. Doesn’t this reflect the contradictions in our society? While those who shared in the suffering of Christ’s cross within Christianity groaned under social maladaptation, the children of those who thrived under the Japanese Empire attended the University of Tokyo, secured positions in church denominations and academies after liberation, and enjoyed prosperity under the US military government centered around the University of Minnesota. Judging this situation impartially, “the cross erected on the blood-soiled land still bears the groaning Jesus who has not yet been resurrected.“

The international acclaim for German political theology is not coincidental but stems from profound self-examination and painful reflection on the past immediately following World War II. Has South Korea engaged in such reflection and self-examination? Opportunities were given, yet were they ignored or evaded? Faith that does not partake in Christ’s suffering on the cross, a faith not deeply rooted in history, turns into a myth, and the Trinitarian revelation of God fails to firmly root itself in this land, degenerating into yet another doctrinal rhetoric.

Today’s church often fails to serve as a model for the world, perhaps because it has lost the “God of Pathos,” the “Liberating God” who engages and ultimately leads to liberation through shared suffering. The Trinitarian God is only faintly perceived through the scars of Jesus Christ. I believes that for Christians in this land to have a historically rooted faith in God’s redemptive work, a profound reflection on God who shares in our suffering is urgently needed.

2. Resistance through Black Theology in North America and the Mt. Sion Community’s Praise

2.1. Formation and Development of Black Theology in North America

Black Theology in North America emerged from the reflection on how millions of black slaves, trafficked from Africa across the Atlantic to the American continent, encountered God in their struggle for religious freedom. Despite enduring inhumane conditions, exploitation, unpaid labor, violence, sexual assault, famine, and premature death, and despite slaveholders’ attempts to dismantle familial bonds, African slaves approached the gospel truth more closely by radically reinterpreting the Christianity of their white masters. They realized that “God does not discriminate among people; He created and loves all humans as His children” and that “Jesus died and was resurrected to free everyone,” truths foundational to the gospel.

However, white slaveholders could not accept that black slaves were living lives more fitting to the gospel of Christ, leading to severe persecution. Whites prohibited black slaves from having their own worship services, enforcing harsh punishments for violations. Consequently, black slaves would gather secretly in secluded places like “hush harbors” after exhausting days of labor to hold their own clandestine prayer meetings, where they truly experienced God. In these gatherings, they fully embraced the Hebrew slaves’ cries and desires for deliverance under Egyptian oppression, and reinterpreted Jesus’ death and resurrection not as a passive acceptance of suffering and hope for the afterlife but as a source of strength to fight against present evils. American theologian James Cone summarized this by saying, “Believing in heaven was a refusal to accept hell on earth.”

This new religious heritage from black slaves, characterized by a unique style of preaching and prophetic sharpness, was monumental in the tradition of the struggle for freedom. It was refined into Black Liberation Theology by figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and theologians like James Cone. Cone defined the work of Black Liberation Theology as “linking the power of liberation and the essence of the gospel with Jesus Christ within the existential circumstances of an oppressed community, and rationally studying the presence of God in this world as a reasoned academic discipline.” For Cone, the activity of God was synonymous with liberation, and Black Liberation Theology questioned the meaning of God’s presence and activity—liberation—in this world. Additionally, black theologians proclaimed “the blackness of God,” arguing that the historical life of joys and sorrows of black people provides valuable insights into the nature of God. They interpreted the God of the oppressed as a transformative deity who “breaks the chains of slavery.”

2.2. Comparing the Struggles of Faith through Black Spiritual and New Song

The chains of the slaves have finally broken. Finally broken. Finally broken.

The chains of the slaves have finally broken.

I will praise God till I die.

These black spirituals were not mere leisure activities for African American slaves but were specific expressions of active resistance. Through these religious songs, they articulated that God is “the one who breaks the chains of slaves” in the most accessible way for them. Moreover, black spirituals demonstrated that their faith was not just a rational discourse but something emotive and dramatic. Biblical themes within these spirituals, combined with African rhythms, melodies, and forms of lamentation, uniquely expressed the real sufferings of black slaves.

James Cone argued that in black spirituals, God’s own Spirit enters into the lives of the people, providing them with the presence of God and emotions of accomplishment and courage. In other words, black spirituals did not offer answers but were a primary way to experience and confirm that “your lives matter,” celebrating not a question of God’s existence but the joy that “God was with us in our struggle.” For many illiterate black slaves, spirituals were the primary access to God’s word, offering hope that they would reunite in Heaven despite the harsh realities of their diaspora. This hope allowed them to maintain their humanity even in the depths of despair.

Oh freedom! Oh freedom! Oh freedom!

I love freedom.

Once I was a slave.

But when I die, I’ll be buried in my grave

And go home to my Lord and be free!

Meanwhile, the life and experience of Koreans, or rather ‘Josenjing’, under Japanese imperialism were comparable to those of the black slaves. The Japanese sought to annihilate the Korean spirit through brutal tactics and forced Koreans to worship the “Emperor Father” instead of “God the Father,” and attempted to assimilate all Korean churches into the Japanese Christian Church of Korea. Thus, the Christianity of Japan produced false messages of oppression and exploitation, similar to those propagated by white slaveholders, and oppressed Korean Christians came to understand the gospel of Jesus more genuinely as a message of liberation and freedom. Consequently, many Korean Christians secretly gathered in hidden places for worship where God met with them.

Particularly noteworthy is the Mt. Sion Community’s resistance against Japanese imperialism through ‘New Song’, akin to black spiritual. The new song of the Mt. Sion Community was based on Revelation 14:3, “They sang a new song before the throne and before the four living creatures and the elders. No one could learn the song except the 144,000 who had been redeemed from the earth.” They created songs by adapting biblical verses to fit their context, empowering the oppressed Korean Christians with strength and courage. Up until 1944, 32 new songs were composed, and today, about 150 selected songs are still sung. Here, we will examine a few of the initial 32 songs.

The first chapter was received on the evening of April 25, 1944, the day Pastor Joo Ki-chul was executed and buried after dying in a Pyongyang prison, indicating that they had metaphorically seized the Japanese nation through faith.

Elohim

Glory of the Trinity

Forever and ever,

All creations between heaven and earth,

And countless saints,

Sing praises together.

New Song Chapter 3, based on Revelation 17:14 and composed in May 1944, used a Japanese military song tune to express the joy of having already overcome Japan by seizing their military songs. It was unimaginable during the severe oppression of 1944, yet they sang this song exuberantly on the train from Cheongdo to Daegu after liberation, celebrating the prophesied victory.

Soldiers of Jesus

Verse 1: By the power of the Trinity and the merits of the cross, Become soldiers of Jesus among all nations, Dedicate my life for the name of the Lord, to serve Him forever.

Verse 2: The Savior who redeemed the people of Mt. Sion with boundless love, We who are redeemed, Dedicate our strength and zeal, to faithfully serve forever.

(Further verses omitted)

The 9th Song, “Occupation Song of the Small Horn,” composed in September 1944 based on Daniel 7:8, 11, 12, commemorates the complete annihilation of the Japanese forces at Saipan Island on July 7, 1944. The Mt. Sion Community celebrated every Japanese defeat without prior coordination by secretly gathering in Surak to hold services commemorating Japan’s defeat.

Conquest of the Small Horn

Verse 1: By the power of God who conquered Saipan Island, Proclaim His great majesty to the whole world, The Lord of all, the King of kings, tramples down the enemy, He has redeemed us, so shout Hosanna.

(Further verses omitted)

Finally, New Song Chapter 13, based on Revelation 7:2 and 17:14 and composed in September 1944, celebrates becoming “the chosen people” through Christ’s suffering.

Chosen (The Morning when the Glory of Sion Shines)

Verse 1: As the glory of Sion shines in the morning, this dark land brightens, Sorrow and misery turn to joy, the righteous sun shines forth.

Verse 2: As the glory of Sion shines in the morning, the bound servants gain freedom, The great love of the Triune God before creation, all peoples of the new world rejoice.

Verse 3: Joyfully, all people come to drink from the springs and streams of David, With thousands of angels and saints, praising the grace of the Savior.

Verse 4: The sinful earth is burned away, and the peace of Eden is restored, Before the glorious throne of the Trinity, all nations of the world worship.

These songs played a crucial role in nurturing hope and resilience among the oppressed, similar to how black spirituals empowered African American slaves.

2.3. The “God Who Breaks the Chains of Slavery” in Black Spiritual and New Song of the Mt. Sion Community

For Korean theology to truly reflect the Korean experience, as theologian James Cone suggested, theology must engage with the concrete lives of its practitioners and cannot be objective. Korean theology must begin by examining how God encountered those on this land struggling for freedom.

The Christians of colonial Korea identified with the faith in “God Who Breaks the Chains of Slavery,” celebrated in black spirituals, triumphing in their faith in the saving history and the living presence of the Triune God even under severe Japanese exploitation and oppression. However, it is disheartening to note that today’s South Korean society still seems to be struggling for the freedom and liberation from the shadows of Japanese imperialism and pro-Japanese forces. Could it be that the church’s “Hallelujahs” have drowned out the lifelong cries of the comfort women, who endured inhumane exploitation comparable to that of black slaves—unpaid labor, violence, sexual violence, and the destruction of familial ties? Are the cold chains that oppressed and exploited our fathers, sisters, and brothers still tightly wrapped around us? Is it because our contemporary struggles for freedom in faith are not as desperate as those of the black slaves? Have we truly made the Hebrew slaves’ cries under Egyptian oppression and their longing for salvation our own?

The joyful proclamation of the “Liberating God” sung by the Mt. Sion Community amidst the specific historical context of Japanese oppression reflects a distinct practice compared to the general hymnals produced by major or minor denominations with unique biblical interpretations. During the Japanese occupation, they identified their oppressors and formed a faith community, creating community-specific hymnals, a practice not documented elsewhere; the New Song of the Sion Community are unique in this respect.

Reverend Jong Woo Kim

Gyeongju Church

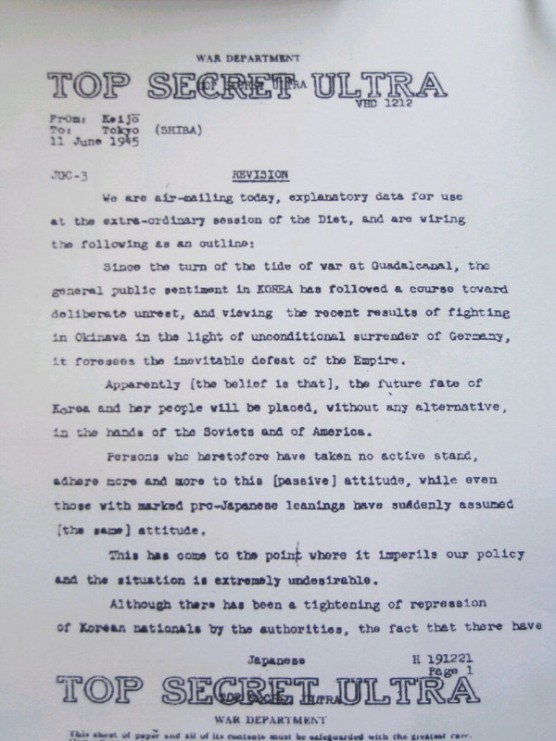

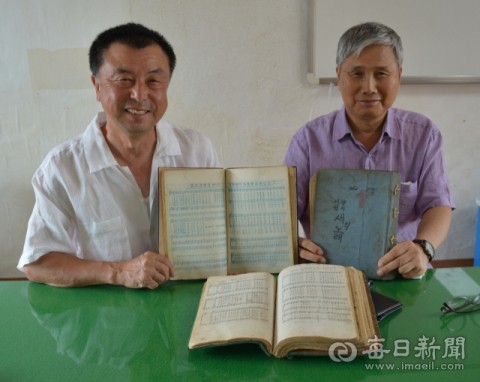

* Gyeongju Church continues the legacy of the Mt. Sion Presbyterian Church, founded on August 20, 1945, by Christians in the Yeongnam region who had been sentenced to death for refusing the emperor and shrine worships imposed by the Japanese. The faith community before liberation was established on April 25, 1944, and the following year, on May 21, 1945, 33 leaders were arrested and sentenced to death, but were released from prison on August 16 of the same year. After the Korean War, the church relocated to Gyeongju in 1956, and its related history was introduced nationally and internationally in 2004 after the declassification of highly confidential documents by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 60 years later.